I just read an article about “green marketing” and how the manufacturer should downplay the green aspects of a product because “very few Americans have ever bought stuff because they want to

save the planet.”[1]

And I agree that most people just want their stuff, not a sermon.

But when I hear something along the lines of “we love your fabrics, but we’re looking for a particular shade of …” my heart drops – because I realize the speaker does not really believe that his

fabric choices are making a direct impact on him or his clients. He does not believe that buying a product that pollutes our groundwater, contributes to global warming, contains chemicals which are known to be harmful to humans (and which might well have long term impacts on him), and all too often employs children who should be in school helping us fight the enormous problems we face – well, he doesn’t believe each purchase simply ensures that the same products will continue to be made!

Because what you buy is what gets produced. It may be a long, circuitous way of making a

personal impact on you, but it happens nevertheless.

Why don’t people recognize this?

Green lifestyle expert Danny Seo says the main reason people choose not to buy green is: they’re selfish.[2] If there is not a tangible benefit to wearing organic cotton, or changing to organic bedding, Seo says people literally will not buy into it. “All you know is that you have done something better for the planet. We are selfish, and want to know what we are getting out of it. That is why something like organic cotton will never work, because there is no direct link to why people should want to do this.” And unlike a Prius, organic clothing or bedding isn’t something one can point to and use to improve their status – or promote their “greener than thou” lifestyle.

But Danny Seo doesn’t know about textile processing – because that organic cotton, if processed conventionally, contains chemicals – 27% by weight of the fabric to be exact – which most definitely will allow you to make a direct link to what people are getting out of it – from asthma and allergies to cancers and worse.

To cite just a few examples:

- The American Contact Dermatitis Society has an interesting web

site for people suffering from formaldehyde resins in fabrics[3], - studies have found dioxin which leached from clothing – a potent

carcinogen – on the skin of participants [4] - and women working in textile factories which produce acrylic

fibers have seven times the rate of breast cancer as the normal population[5].

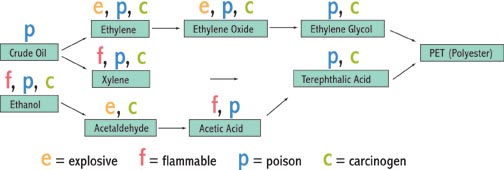

Textile processing uses some of the most potent and dangerous chemicals known – and they remain in the fabrics we live with. This becomes part of the chemical soup we’re all exposed to each day, and which we believe is changing us in many ways, not all for the better. We don’t just absorb synthetic chemicals one at a time during the day. We’re exposed to hundreds of chemicals as a result of using a wide array of consumer products, many of which contain the same chemicals as are found in fabrics. We are exposed to a variety of stressors – and textiles are one of the stressors, among others such as:

- Automotive exhaust

- Cleaning products

- Chemicals in treated water

- Cosmetics

- Environmental pollution

- Food

- Insect repellents

- Prescription drugs

- solvents

- Ultraviolet radiation

As we absorb tiny amounts of chemicals repeatedly from multiple sources, they might add up until they reach a tipping point. Add to this what Drs. Anita and Paul Clement call the “black hole” of ignorance about a key fact in toxicology: that toxins make each other worse. “A small dose of mercury that kills 1 in 100 rats and a dose of aluminum that kills 1 in 100 rats, when combined, have a striking effect: all the rats die.“

So how can you, as an individual, change it – how can one person do anything to change the world? Margaret Meade says that committed people, banding together, is the only thing that really

ever has.

The writer Fritjof Capra says that we need to be governed “by a metaphor that says we are part of a continuously evolving and interrelated system”. We need to start thinking of the world as a system, a cyclical system of interconnections, a web of connections— literally “the web of life.”

And it must be understood that this is a long-term project, not to be mistaken for a marketing trend like one furnishings manufacturer told us. (“Green?” he said. “Yes, well, we did that last year, but we’re doing something really exciting this year!”) In fact, green is only a part of it, a central part that must deal with environmentally benign materials and processes, restoration, recycling, reclaiming: all those things we have to do to remedy the damage we’ve done to the natural environment and to ourselves in it.

Hope for the future springs from witnessing small reversals of the damage we have caused, as Victor Papanek says in The Green Imperative. These times, he says, also call for a sense of optimism and a willingness to act without full understanding but with a faith in the effect of small individual actions on the global picture.

Remember that each time you purchase something, you’re ensuring that the product you bought will keep being produced, in the same way. If you support new ideas, find creative ways to use something or insist that what you buy meets certain parameters, then new research will be done to

meet consumer demand and new processes will be developed that don’t leave a legacy of destruction.

Lots of people, individually and together, made a difference in the way our foods are grown and processed. Organic foods went from gnarly to beautiful, and now we’re becoming healthier and our land is being replenished. It can be done if the individual believes in his own importance, and believes that each purchasing decision is a vote – for clean air and water and safe products – a vote literally for our future. Or not.

[1]

Shelton, Suzanne, “Green Marketing and the Death of Curmudgeonly Contrariness”,

GreenBiz, May 19, 2011.

[2]

Kate Rogers, “Why People Opt Against Going Green”, FOXBusiness, November 4,

2011; http://www.foxbusiness.com/personal-finance/2011/11/04/why-people-opt-against-going-green/

[4] “Dioxins and Dioxin-like Persistent Organic Pollutants in Textiles and Chemicals in the

Textile Sector” Bostjan Krizanec and Alenka Majcen Le Marechal,

Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, Smetanova 17, SI-2000

Maribor, Slovenia; January 24, 2006

[5] Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2010,

67:263-269 doi: 10.1136/oem.2009.049817

SEE ALSO: http://www.breastcancer.org/risk/new_research/20100401b.jsp

AND http://www.medpagetoday.com/Oncology/BreastCancer/19321