I just read the article by Team Treehugger on Planet Green on what to look for if you’re interested in green furniture. And sure enough, they talked about the wood (certified sustainable – but without any explanation about why Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certified wood should be a conscientious consumers only choice), reclaimed materials, design for disassembly, something they call “low toxicity furniture”, buying vintage…the usual suspects. Not once did they mention your fabric choice.

Of course, all these are important considerations and like most green choices, there are tradeoffs and degrees of green. But if we look at the carbon footprint of an average upholstered sofa and see what kind of energy requirements are needed to produce that sofa, we can show you how your fabric choice is the most important choice you can make in terms of embodied energy. Later on (next week’s post) we’ll take a look at what your choices mean in terms of toxicity and environmental degredation.

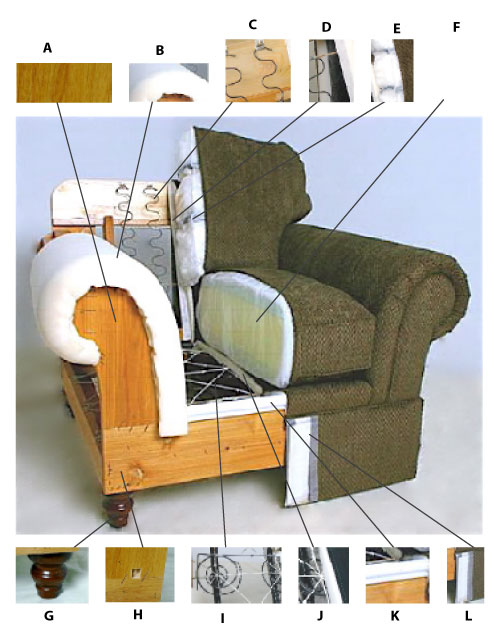

These are the components of a typical sofa:

- Wood

- Foam (most commonly) or other cushion filling

- Fabric

- Miscellaneous:

- Glue

- Varnish/paint

- Metal springs

- Thread

- Jute webbing

- Twine

- WOOD: A 6 foot sofa uses about 32 board feet of lumber (1) . For kiln dried maple, the embodied energy for 32 board feet is 278 MJ. But if we’re looking at a less expensive sofa which uses glulam (a laminated lumber product), the embodied energy goes up to 403 MJ.

- FOAM: Assume 12 cubic feet of foam is used, with a density of 4 lbs. per cubic foot (this is considered a good weight for foam); the total weight of the foam used is 48 lbs. The new buzz word for companies making upholstered furniture is “soy based foam” (an oxymoron which we’ll expose in next week’s post), which is touted to be “green” because (among other things) it uses less energy to produce. Based on Cargill Dow’s own web site for the BiOH polyol which is the basis for this new product, soy based foam uses up to 60% less energy than does conventional polyurethane foams. Companies which advertise foam made with 20% soy based polyols use 1888 MJ of energy to create 12 cubic feet of foam, versus 2027 MJ if conventional polyurethane was used. For our purposes of comparison, we’ll use the lower energy amount of 1888 MJ and give the manufacturers the benefit of the doubt.

- FABRIC: Did you know that the decorative fabric you choose to upholster your couch is not the only fabric used in the construction? Here’s the breakdown for fabric needed for one sofa:

- 25 yards of decorative fabric

- 20 yards of lining fabric

- 15 yards of burlap

- 10 yards of muslin

TOTAL amount of fabric needed for one sofa: 70 yards!

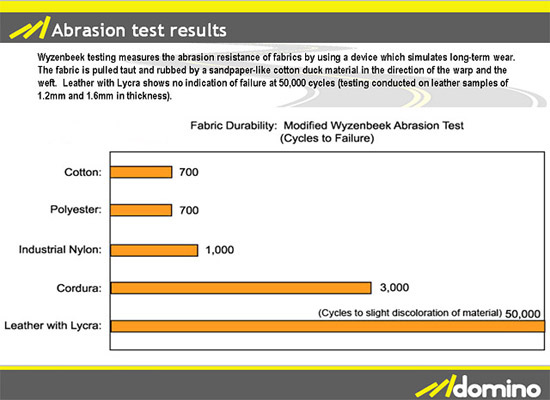

Using data from various sources (see footnotes below), the amount of energy needed to produce the fabric varies between 291 MJ (if all components were made of hemp, which has the lowest embodied energy) and 7598 MJ (if all components were made of nylon, which has the highest embodied energy requirements). If we choose the most commonly used fibers for each fabric component, the total energy used is 2712 MJ:

| fiber | Embodied energy in MJ | |

| 25 yards decorative fabric/ 22 oz lin. yd = 34.0 lbs | polyester | 1953 |

| 20 yards lining fabric / 15 oz linear yard = 19 lbs | cotton | 469 |

| 15 yards burlap / 10 oz linear yard = 9.4 lbs | hemp | 41 |

| 10 yards muslin / 7 oz linear yard = 4.4 lbs | polyester | 249 |

| TOTAL: | 2712 |

I could not find any LCA studies which included the various items under “Miscellaneous” so for this example we are discounting that category. It might very well impact results, so if anyone knows of a study which addresses these items please let us know!

So we’re looking at three components (wood, foam and fabric), only two of which most people seem to think are important in terms of upholstered furniture manufacture. But if we put the results in a table, it’s suddenly very clear that fabric is the most important consideration – at least in terms of embodied energy:

| Embodied energy in MJ | |||

| WOOD: | 32 board feet, kiln dried maple | 278 | |

| FOAM: | 12 cubic feet, 20% bio-based polyol | 1888 | |

| SUBTOTAL wood and foam: | 2166 | ||

| FABRIC: | FIBER: | ||

| 25 yards uphl fabric/ 22 oz lin. yd = 34.0 lbs | polyester | 1953 | |

| 20 yards lining fabric / 15 oz linear yard = 19 lbs | cotton | 469 | |

| 15 yards burlap / 10 oz linear yard = 9.4 lbs | hemp | 41 | |

| 10 yards muslin / 7 oz linear yard = 4.4 lbs | polyester | 249 | |

| SUBTOTAL, fabric: | 2712 |

If we were to use the most egregious fabric choices (nylon), the subtotal for the energy used to create just the fabric would be 7598 MJ – more than three times the energy needed to produce the wood and foam! This is just another instance where fabric, a forgotten component, makes a profound impact.

(1) From: “Life Cycle Analysis of Wood Products: Cradle to Gate LCIof residential wood building material”, Wood and Fiber Science, 37 Corrim Special Issue, 2005, pp. 18 – 29.

(2) Data for embodied energy in fabrics:

“Ecological Footprint and Water Analysis of Cotton, Hemp and Polyester”, Stockholm Environment Institute, 2005

Composites Design and Manufacture, School of Engineering, University of Plymouth UK, 2008, http://www.tech.plym.ac.uk/sme/mats324/mats324A9%20NFETE.htm

Study: “LCA: New Zealand Merino Wool Total Energy Use”, Barber and Pellow.

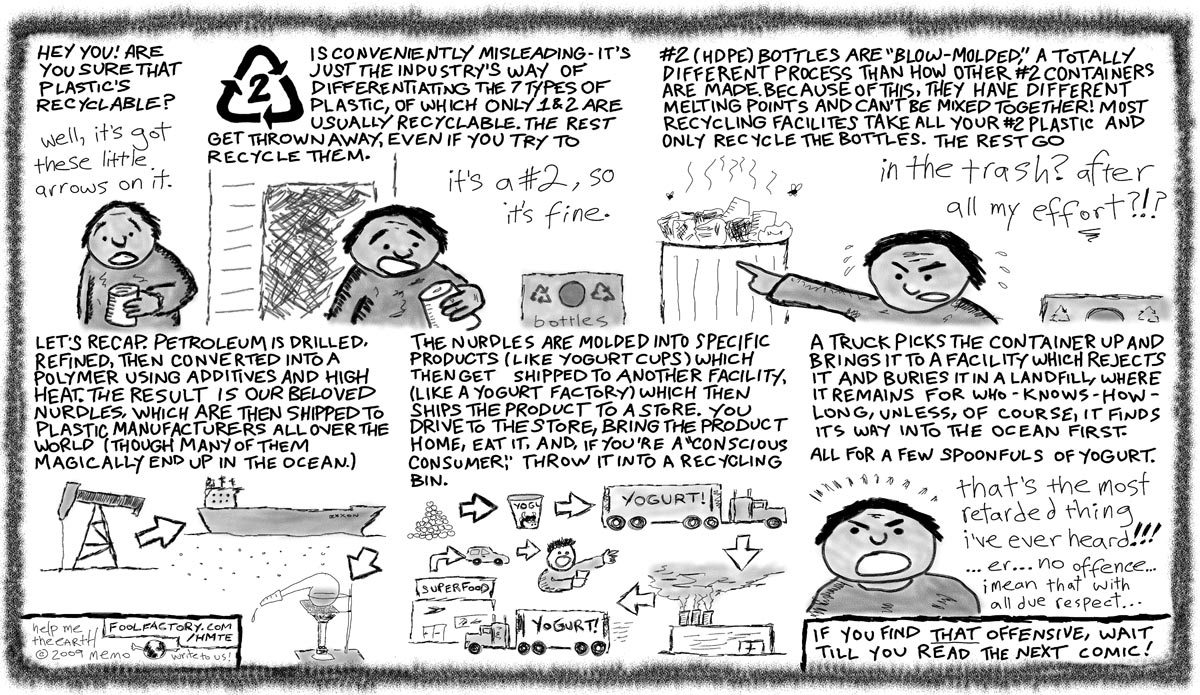

From Help me! – the earth by

From Help me! – the earth by