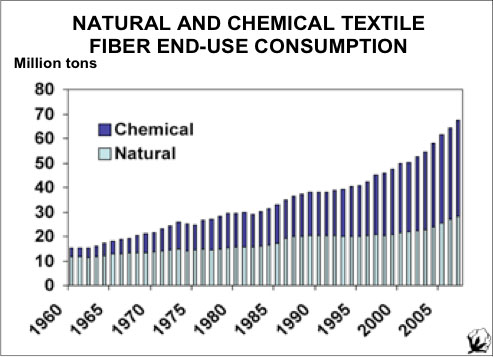

Since the 1960s, the use of synthetic fibers has increased dramatically, causing the natural fiber industry to lose much of its market share. In December 2006, the United Nations General Assembly declared 2009 the International Year of Natural Fibres (IYNF); a year-long initiative focused on raising global awareness about natural fibers with specific focus on increasing market demand to help ensure the long-term sustainability for farmers who rely heavily on their production.

Since I have recently been ranting about the plastics industry I thought it was time to turn to natural fibers, which have a history of being considered the highest quality fibers, valued for their comfort, soft hand and versatility. They also carry a certain cachet: cashmere, silk taffeta and 100% pure Sea Island cotton convey different images than does 100% rayon, pure polyester or even Ultrasuede, don’t they? And natural fibers, being a bit of an artisan product, are highly prized especially in light of campaigns by various trade associations to brand its fiber:  “the fabric of our lives” from Cotton, Inc. and merino wool with the pure wool label are two examples.

“the fabric of our lives” from Cotton, Inc. and merino wool with the pure wool label are two examples.

Preferences for natural fibers seem to be correlated with income; in one study, people with higher incomes preferred natural fibers by a greater percentage than did those in lower income brackets. Cotton Incorporated funded a study that demonstrated that 66% of all women with household incomes over $75,000 prefer natural fibers to synthetic.

What are the reasons, according to the United Nations, that make natural fibers so important? As the UN website, Discover Natural Fibers says:

- Natural fibers are a healthy choice.

- Natural fiber textiles absorb perspiration and release it into the air, a process called “wicking” that creates natural ventilation. Because of their more compact molecular structure, synthetic fibers cannot capture air and “breathe” in the same way. That is why a cotton T-shirt is so comfortable to wear on a hot summer’s day, and why polyester and acrylic garments feel hot and clammy under the same conditions. (It also explains why sweat-suits used for weight reduction are made from 100% synthetic material.) The bends, or crimp, in wool fibers trap pockets of air which act as insulators against both cold and heat – Bedouins wear thin wool to keep them cool. Since wool can absorb liquids up to 35% of its own weight, woollen blankets efficiently absorb and disperse the cup of water lost through perspiration during sleep, leaving sheets dry and guaranteeing a much sounder slumber than synthetic blankets.

- The “breathability” of natural fiber textiles makes their wearers less prone to skin rashes, itching and allergies often caused by synthetics. Garments, sheets and pillowcases of organic cotton or silk are the best choice for children with sensitive skins or allergies, while hemp fabric has both a high rate of moisture dispersion and natural anti-bacterial properties. Studies by Poland’s Institute of Natural Fibers have shown that 100% knitted linen is the most hygienic textile for bed sheets – in clinical tests, bedridden aged or ill patients did not develop bedsores. The institute is developing underwear knitted from flax which, it says, is significantly more hygienic than nylon and polyester. Chinese scientists also recommend hemp fiber for household textiles, saying it has a high capacity for absorption of toxic gases.

- Natural fibers are a responsible choice.

- Natural fibers production, processing and export are vital to the economies of many developing countries and the livelihoods of millions of small-scale farmers and low-wage workers. Today, many of those economies and livelihoods are under threat: the global financial crisis has reduced demand for natural fibers as processors, manufacturers and consumers suspend purchasing decisions or look to cheaper synthetic alternatives.

- Almost all natural fibers are produced by agriculture, and the major part is harvested in the developing world.

- For example, more than 60% of the world’s cotton is grown in China, India and Pakistan. In Asia, cotton is cultivated mainly by small farmers and its sale provides the primary source of income of some 100 million rural households.

- In India and Bangladesh, an estimated 4 million marginal farmers earn their living – and support 20 million dependents – from the cultivation of jute, used in sacks, carpets, rugs and curtains. Competition from synthetic fibers has eroded demand for jute over recent decades and, in the wake of recession, reduced orders from Europe and the Middle East could cut jute exports by 20% in 2009.

- Silk is another important industry in Asia. Raising silkworms generates income for some 700 000 farm households in India, while silk processing provide jobs for 20 000 weaving families in Thailand and about 1 million textile workers in China. Orders of Indian silk goods from Europe and the USA are reported to have declined by almost 50% in 2008-09.

- Each year, developing countries produce around 500 000 tonnes of coconut fiber – or coir – mainly for export to developed countries for use in rope, nets, brushes, doormats, mattresses and insulation panels. In Sri Lanka, the single largest supplier of brown coir fiber to the world market, coir goods account for 6% of agricultural exports, while 500 000 people are employed in small-scale coir factories in southern India.

- Across the globe in Tanzania, government and private industry have been working to revive once-booming demand for sisal fiber, extracted from the sisal agave and used in twine, paper, bricks and reinforced plastic panels in automobiles. Sisal cultivation and processing in Tanzania directly employs 120 000 people and the sisal industry benefits an estimated 2.1 million people. However, the global slowdown has cut demand for sisal, forced a 30% cut in prices, and led to mounting job losses.

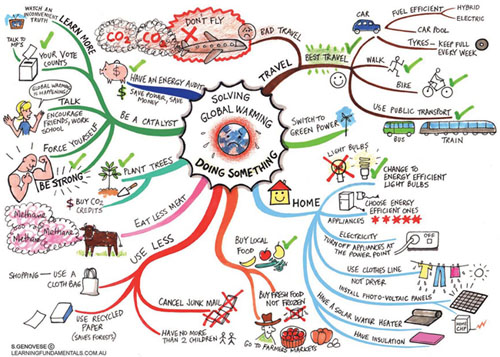

- Natural fibers are a sustainable choice.

- Natural fibers will play a key role in the emerging “green” economy based on energy efficiency, the use of renewable feed stocks in bio-based polymer products, industrial processes that reduce carbon emissions and recyclable materials that minimize waste. Natural fibers are a renewable resource, par excellence – they have been renewed by nature and human ingenuity for millennia. They are also carbon neutral: they absorb the same amount of carbon dioxide they produce. During processing, they generate mainly organic wastes and leave residues that can be used to generate electricity or make ecological housing material. And, at the end of their life cycle, they are 100% biodegradable.

- An FAO study estimated that production of one ton of jute fiber requires just 10% of the energy used for the production of one ton of synthetic fibers (since jute is cultivated mainly by small-scale farmers in traditional farming systems, the main energy input is human labor, not fossil fuels).

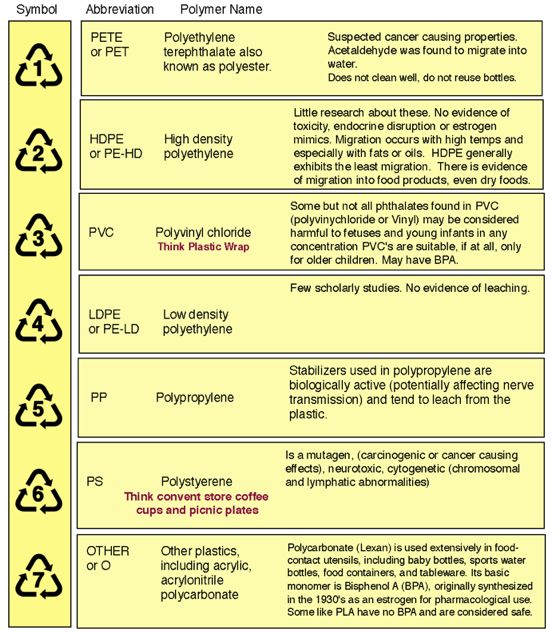

- Processing of some natural fibers can lead to high levels of water pollutants, but they consist mostly of biodegradable compounds, in contrast to the persistent chemicals, including heavy metals, released in the effluent from synthetic fiber processing. More recent studies have shown that producing one ton of polypropylene – widely used in packaging, containers and cordage – emits into the atmosphere more than 3 ton of carbon dioxide, the main greenhouse gas responsible for global warming. In contrast, jute absorbs as much as 2.4 tonnes of carbon per tonne of dry fiber.

- The environmental benefits of natural fiber products accrue well beyond the production phase. For example, fibers such as hemp, flax and sisal are being used increasingly as reinforcing in place of glass fibers in thermoplastic panels in automobiles. Since the fibers are lighter in weight, they reduce fuel consumption and with it carbon dioxide emissions and air pollution.

- But where natural fibers really excel is in the disposal stage of their life cycle. Since they absorb water, natural fibers decay through the action of fungi and bacteria. Natural fiber products can be composted to improve soil structure, or incinerated with no emission of pollutants and release of no more carbon than the fibers absorbed during their lifetimes. Synthetics present society with a range of disposal problems. In land fills they release heavy metals and other additives into soil and groundwater. Recycling requires costly separation, while incineration produces pollutants and, in the case of high-density polyethylene, 3 tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions for every tonne of material burnt. Left in the environment, synthetic fibers contribute, for example, to the estimated 640 000 tonnes of abandoned fishing nets and gear in the world’s oceans.

- Natural fibers are a high-tech choice.

- Natural fibers have intrinsic properties – mechanical strength, low weight and low cost – that have made them particularly attractive to the automobile industry.

- In Europe, car makers are using mats made from abaca, flax and hemp in press-molded thermoplastic panels for door liners, parcel shelves, seat backs, engine shields and headrests.

- For consumers, natural fiber composites in automobiles provide better thermal and acoustic insulation than fiberglass, and reduce irritation of the skin and respiratory system. The low density of plant fibers also reduces vehicle weight, which cuts fuel consumption.

- For car manufacturers, the moulding process consumes less energy than that of fibreglass and produces less wear and tear on machinery, cutting production costs by up to 30%. The use of natural fibres by Europe’s car industry is projected to reach 100 000 tonnes by 2010. German companies lead the way. Daimler-Chrysler has developed a flax-reinforced polyester composite, and in 2005 produced an award-winning spare wheel well cover that incorporated abaca yarn from the Philippines. Vehicles in some BMW series contain up to 24 kg of flax and sisal.

Released in July 2008, the Lotus Eco Elise (pictured above) features body panels made with hemp, along with sisal carpets and seats upholstered with hemp fabric. Japan’s carmakers, too, are “going green”. In Indonesia, Toyota manufactures door trims made from kenaf and polypropylene, and Mazda is using a bioplastic made with kenaf for car interiors.

Released in July 2008, the Lotus Eco Elise (pictured above) features body panels made with hemp, along with sisal carpets and seats upholstered with hemp fabric. Japan’s carmakers, too, are “going green”. In Indonesia, Toyota manufactures door trims made from kenaf and polypropylene, and Mazda is using a bioplastic made with kenaf for car interiors.

- In Europe, car makers are using mats made from abaca, flax and hemp in press-molded thermoplastic panels for door liners, parcel shelves, seat backs, engine shields and headrests.

- Worldwide, the construction industry is moving to natural fibres for a range of products, including light structural walls, insulation materials, floor and wall coverings, and roofing. Among recent innovations are cement blocks reinforced with sisal fibre, now being manufactured in Tanzania and Brazil. In India, a growing shortage of timber for the construction industry has spurred development of composite board made from jute veneer and coir ply – studies show that coir’s high lignin content makes it both stronger and more resistant to rotting than teak. In Europe, hemp hurd and fibres are being used in cement and to make particle boards half the weight of wood-based boards. Geotextiles are another promising new outlet for natural fibre producers. Originally developed in the Netherlands for the construction of dykes, geotextile nets made from hard natural fibres strengthen earthworks and encourage the growth of plants and trees, which provide further reinforcement. Unlike plastic textiles used for the same purpose, natural fibre nets – particularly those made from coir – decay over time as the earthworks stabilize.

- Natural fibers have intrinsic properties – mechanical strength, low weight and low cost – that have made them particularly attractive to the automobile industry.

- Natural fibers are a fashionable choice.

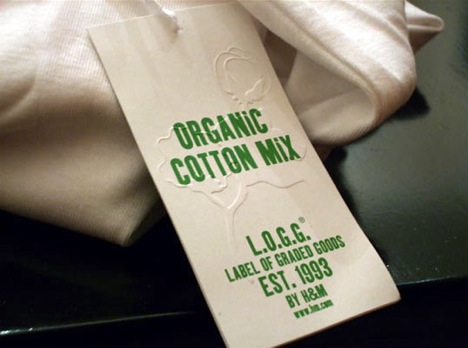

- Natural fibers are at the heart of a fashion movement that goes by various names: sustainable, green, uncycled, ethical, eco-, even eco-environmental. It focuses fashion on concern for the environment, the well-being of fiber producers and consumers, and the conditions of workers in the textile industry. Young designers now offer “100% carbon neutral” collections that strive for sustainability at every stage of their garments’ life cycle – from production, processing and packaging to transportation, retailing and ultimate disposal. Preferred raw materials include age-old fibres such as flax and hemp, which can be grown without agrochemicals and produce garments that are durable, recyclable and biodegradable. Fashion collections also feature organic wool, produced by sheep that have not been exposed to pesticide dips, and “cruelty-free” wild silk, which is harvested – unlike most silk – after the moths have left their cocoons.

- The Global Organic Textile Standard (GOTS) sets strict standards on chemicals permitted in processing, on waste water treatment, packaging material and technical quality parameters, on factory working conditions and on residue testing.

- Sustainable fashion intersects with the “fair trade” movement, which offers producers in developing countries higher prices for their natural fibres and promotes social and environmental standards in fibre processing. Fair trade fashion pioneers are working with organic cotton producers’ cooperatives in Mali, hand-weavers groups in Bangladesh and Nepal, and alpaca producers in Peru. A major UK chain store launched in 2007 a fair trade range of clothing that uses cotton “ethically sourced” from farmers in the Gujarat region of India. It has since sold almost 5 million garments and doubled sales in the first six months of 2008.

- Another dimension of sustainable fashion is concern for the working conditions of employees in textile and garment factories, which are often associated with long working hours, exposure to hazardous chemicals used in bleaching and dyeing, and the scourge of child labor. The recently approved (November 2008) Global Organic Textile Standard, widely accepted by manufacturers, retailers and brand dealers, includes a series of “minimum social criteria” for textile processing, including a prohibition on the use of child labor, workers’ freedom of association and right to collective bargaining, safe and hygienic working conditions, and “living wages”.

For the next few weeks I’ll talk about various fiber types, starting with my favorite, hemp.