In January 2009, new blue uniforms were issued to Transportation Security Administration officers at hundreds of airports nationwide. [1] The new uniforms – besides giving officers a snazzy new look – also gave them skin rashes, bloody noses, lightheadedness, red eyes, and swollen and cracked lips, according to the American Federation of Government Employees, the union representing the officers. “We’re hearing from hundreds of TSOs that this is an issue,” said Emily Ryan, a spokeswoman for the union.

The American Federation of Government Employees blames formaldehyde.

In 2008, an Ohio woman filed suit against Victoria’s Secret, alleging she became “utterly sick” after wearing her new bra. In her lawsuit, the plaintiff said the rash she suffered was “red hot to the touch, burning and itching.” As more people came forth (600 to be exact) claiming horrific skin reactions (and permanent scarring to some) as a result of wearing Victoria Secret’s bras, lawsuits were filed in Florida and New York – after the lawyers found formaldehyde in the bras.

For years the textile industry has been using finishes on fabric that prevents wrinkling – usually a formaldehyde resin. Fabrics are treated with urea-formaldehyde resins to give them all sorts of easy care properties such as:

- Permanent press / durable press

- Anti-cling, anti-static, anti-wrinkle, and anti-shrink (especially shrink proof wool)

- Waterproofing and stain resistance (especially for suede and chamois)

- Perspiration proof

- Moth proof

- Mildew resistant

- Color-fast

That’s why you can find retailers like Nordstrom selling “wrinkle-free finish” dress shirts and L.L. Bean selling chinos that are “great right out of the dryer.” And we’ve been snapping them up, because who doesn’t want to ditch the ironing?

According to the American Contact Dermatitis Society, rayon, blended cotton, corduroy, wrinkle-resistant 100% cotton, and any synthetic blended polymer are likely to have been treated with formaldehyde resins. The types of resins used include urea-formaldehyde, melamine-formaldehyde and phenol-formaldehyde.[2] Manufacturers often “hide” the word “formaldehyde” under daunting chemical names. These include:

- Formalin

- Methanal

- Methyl aldehyde

- Methylene oxide

- Morbicid acid

- Oxymethylene

Not only is formaldehyde itself used, but also formaldehyde-releasing preservatives. Some of these are known by the following names:

- Quaternium-15

- 2-bromo-2nitropropane-1,3-diol

- imidazolidinyl urea

- diazolidinyl urea

Formaldehyde is another one of those chemicals that just isn’t good for humans. Long known as the Embalmer’s Friend for its uses in funeral homes and high school biology labs, formaldehyde effects depend upon the intensity and length of the exposure and the sensitivity of the individual to the chemical. The most common means of exposure is by breathing air containing off-gassed formaldehyde fumes, but it is also easily absorbed through the skin. Increases in temperature (hot days, ironing coated textiles) and increased humidity both increase the release of formaldehyde from coated textiles.

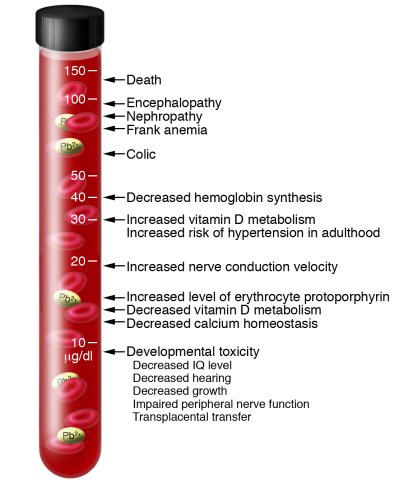

Besides being associated with watery eyes, burning sensations in the eyes and throat, nausea, difficulty in breathing, coughing, some pulmonary edema (fluid in the lungs), asthma attacks, chest tightness, headaches, and general fatigue, as well as the rashes and other illnesses such as reported by the TSA officers, formaldehyde is associated with more severe health issues. For example, it could cause nervous system damage by its known ability to react with and form cross-linking with proteins, DNA and unsaturated fatty acids.13 These same mechanisms could cause damage to virtually any cell in the body, since all cells contain these substances. Formaldehyde can react with the nerve protein (neuroamines) and nerve transmitters (e.g., catecholamines), which could impair normal nervous system function and cause endocrine disruption. [3]

Medical studies have linked formaldehyde exposure with nasal cancer, nasopharyngeal cancer and leukemia. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classified formaldehyde as a human carcinogen. Studies by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the National Cancer Institute (NCI) have found formaldehyde to be a probable human carcinogen and workers with high or prolonged exposure to formaldehyde to be at an increased risk for leukemia (particularly myeloid leukemia) and brain cancer. Read the National Cancer Institute’s factsheet here.

Formaldehyde is one of about two dozen chemical toxins commonly found in homes and wardrobes that are believed by doctors to contribute to Multiple Chemical Sensitivities (MCS). Chemical sensitivities are becoming a growing health problem in the U.S. as the persistent exposure to harsh and toxic chemicals grows. One of the signs of increasing chemical sensitivities is the rise of contact dermatitis caused by formaldehyde resins and other chemicals used in textile finishes. Repeated exposure to even low levels of formaldehyde can create a condition called “sensitization” where the individual becomes very sensitive to the effects of formaldehyde and then even low levels of formaldehyde can cause an “allergic” reaction, such as those suffered by the TSA workers.

Countries such as Austria, Finland, Germany, Norway, Netherlands and Japan have national legislation restricting the presence of formaldehyde in textile products. But in the United States, formaldehyde levels in fabric is not regulated. Nor does any government agency require manufacturers to disclose the use of the chemical on labels. Because it’s used on the fabric, it can show up on any product made from fabric, such as clothing. And it can show up in any room of the house – in the sheets and pillows on the bed. In drapery hanging in the living room. The upholstery on the sofa. Even in the baseball cap hanging by the door.

“From a consumer perspective, you are very much in the dark in terms of what (fabric or) clothing is treated with,” said David Andrews, a senior scientist at the Environmental Working Group, a research and advocacy organization. “In many ways, you’re in the hands of the industry and those who are manufacturing our fabrics. And we are trusting them to ensure they are using the safest materials and additives.” [4]

“The textile industry for years has been telling dermatologists that they aren’t using the formaldehyde resins anymore, or the ones they use have low levels,” said Dr. Joseph F. Fowler, clinical professor of dermatology at the University of Louisville. “Yet despite that, we have been continually seeing patients who are allergic to formaldehyde and have a pattern of dermatitis on their body that tells us this is certainly related to clothing.”

Often it’s suggested that washing the fabric will get rid of the formaldehyde. But think about it: why would a manufacturer put in a wrinkle resistant finish that washes out? If that were the case, your permanent press shirts and sheets would suddenly (after a washing or two) need to be ironed. Do you find that to be the case? Manufacturers work long and hard to make sure these finishes do NOT wash out. At least one study has found that there is no significant reduction in the amount of formaldehyde after two washings. (5)

So we can add formaldehyde to the list of chemicals which surround us, exposing us at perhaps very low levels for many years. What this low level exposure is doing to us has yet to be determined.

[1] “New TSA Unifroms Trigger a Rash of Complaints (Formaldehyde)”, The Washington Post, January 5, 2009, Steve Vogel.

[2] Berrens, L. etal., “Free formaldehyde in textiles in relation to formalin contact sensitivity”

[3] Thrasher JD etal., “Immune activation and autoantibodies in humans with long-term inhalation exposure to formaldehyde,” Archive Env. Health, 45: 217-223, 1990.

[4] “When Wrinkle-Free Clothing Also Means Formaldehyde Fumes”, New York Times, Tara Siegel Bernard, December 10, 2010

(5) Rao S, Shenoy SD, Davis S, Nayak S., “Detection of formaldehyde in textiles by chromotropic acid method”. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2004;70:342-4.