Philosopher George Carlin once said, “Man is only here to give the planet something it didn’t have: Plastic.”

And man has done well: plastic is ubiquitous in our world today and the numbers are growing. We produce 20 times more plastic today than we did 50 years ago.

The production and use of plastics has a range of environmental impacts. Plastics production requires significant quantities of resources: it uses land and water, but the primary resource is fossil fuels, both as a raw material and to deliver energy for the manufacturing process. It is estimated that 8% of the world’s annual oil production is used as either feedstock or energy for production of plastics.

Plastics production also involves the use of potentially harmful chemicals, which include cadmium, lead, PVC, and other pollutants which are added as stabilizers, plasticizers or colorants. Many of these have not undergone environmental risk assessment and their impact on human health and the environment is currently uncertain. Finally, plastics manufacture produces waste and emissions. In the U.S., fourteen percent of airborne toxic emissions come from plastics production. The average plastics plant can discharge as much as 500 gallons of wastewater per minute – water contaminated with process chemicals. (The overall environmental impact varies according to the type of plastic and the production method employed.)

Every second, 200 plastic bottles made of virgin, non-renewable resources are land-filled – and every hour another 2.5 million bottles are thrown away. And though I can’t get a definitive answer about whether the plastics decompose (because although they don’t biodegrade they do photodegrade – when exposed to UV radiation, over time they break down into smaller and smaller bits, leaching their chemical components), most sources, if they do accept that plastic can degrade, admit that nobody knows how long it really takes because most plastics have only been around for 50 years or so – but estimates range into the thousands of years. (To read how scientists make estimates for plastic decomposition rates, click here. )

How do we cope with this plastic onslaught?

Recycling is the most widely recognized concept in solid waste management – and the environmental benefits of recycling plastic are touted elsewhere. I’ll just give you the highlights here:

- It reduces the amount of garbage we send to landfills: Although plastic accounts for only 8% of the waste by weight, they occupy about 20% of the volume in a landfill due to their low bulk density.

- It conserves energy: recycling 1 pound of PET conserves 12,000 BTUs of heat energy; and the production of recycled PET uses 1/3 less energy than is needed to produce virgin PET.

- It reduces greenhouse gas emissions.

- It helps conserve natural resources.

But it should be remembered that some items are much better candidates for recycling than others. Aluminum recycling, for example, uses 95% less energy than producing aluminum from bauxite ore, and aluminum cans can be recycled into new aluminum cans. There is no limit to the amount of times an aluminum container can be recycled. The PET bottle, which is used for everything from water to wine, was patented in 1973 – that’s only 27 years ago! Prior to that most bottles were of glass. Glass, like aluminum, is infinitely recyclable. As late as 1947, virtually 100% of all beverage bottles were returnable; and states with bottle deposit laws have 35 – 40% less litter by volume. I found this image while looking for Earth Day anniversary images, and think it’s a great example of how corporations will slant anything to their purposes. (Please note that the company in question is Coca Cola – I’ll have a lot to say about Coke’s recycling efforts in 2010 in upcoming blog posts):

There are different costs and benefits for other recyclable items: plastic, paper, electronics, motor oil… They each have their own individual problems.

With reference to the textile industry, 60% of all the virgin polyethelene terephthalate (PET) produced globally is used to make fibers, while only 30% goes into bottle production. As I explained in a previous blog, the textile industry has adopted recycled polyester as the fiber of choice to promote its green agenda. What I want to do is expose this choice for what it is: a self-serving attempt to convince the public that a choice of a recycled polyester fabric is actually a good eco choice – when the reality is that this is another case of expediency and greed over any authentic attempts to find a sustainable solution. My biggest complaint with the industry’s position is that there is no attempt made to address the question of water treatment or of chemical use during dyeing and processing of the fibers.

So to begin, let’s look at what plastic recycling means, since there are many misconceptions about recycling plastic – especially plastic bottles from which (some) recycled polyester yarns are made.

In 1970, at the time of the first Earth Day, Gary Anderson won a contest sponsored by Container Corporation of America to present a design which symbolizes the recycling process.  His winning design was a three-chasing-arrows Mobius loop, with the arrows twisting and turning among themselves. Because of the symbol’s simplicity and clarity it became widely used worldwide and is a symbol now recognized by almost everyone. Today almost all plastic containers have the “chasing arrows” symbol. We’re bombarded with that symbol – any manufacturer worth his salt slaps it on their products.

His winning design was a three-chasing-arrows Mobius loop, with the arrows twisting and turning among themselves. Because of the symbol’s simplicity and clarity it became widely used worldwide and is a symbol now recognized by almost everyone. Today almost all plastic containers have the “chasing arrows” symbol. We’re bombarded with that symbol – any manufacturer worth his salt slaps it on their products.

But the symbol itself is meaningless. This symbol is not a government mandated code, and does not imply any particular type or amount of recycled content. Many people think that the “chasing arrows” symbol means the plastic can be recycled – and that too is untrue.

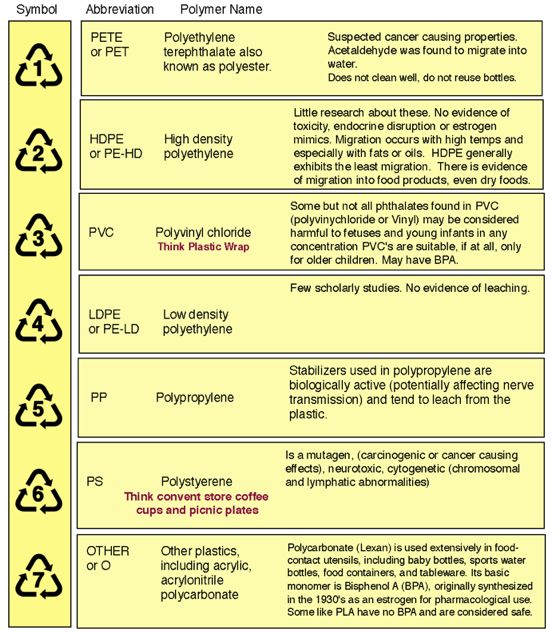

The only useful information in the “chasing arrows” symbol is the number inside the arrows, which indicates the general class of resin used to make the container. There are thousands of types of plastic used for consumer packaging today. In 1988, the Society of the Plastics Industry devised a numbering system to aid in sorting plastics for recycling, because in order to be recycled, each plastic container must be separated by type before it can be used again to make a new product. Of the seven types, only two kinds, polyethelene terephthalate (PET), known as #1, and High Density Polyethelyne (HDPE) – or #2 – are typically collected and reprocessed. Some of these resins are not yet recyclable at all (such as #6 or 7), or they’re recyclable only rarely.

In addition, a resin code might indeed indicate #1 (PET) for example, but depending on the use (yogurt cup vs. soda bottle) it will contain different dyes, plasticizers, UV inhibitors, softeners, or other chemicals.

This mix of additives changes the properties of the plastic, so not all #1 resins can be melted together – further complicating the process. Here’s a list of the seven resin codes and some of the concerns associated with each:

Consumers see the symbol and – thinking it means the plastic can be recycled – drop bottles into recycling bins, feeling they’ve “done their part” and that the used bottle is now part of the infinite loop, becoming a new and valued product. But does the bottle actually get “recycled”, returning to a high value product, staying out of the garbage dump?

Well, uh, . . . not really. Collecting plastic containers in a recycling bin fosters the belief that, like aluminum and glass, the recovered material is converted into new containers. In fact, none of the recovered plastic containers are being made into containers again, but rather into new secondary products, like textiles, parking lot bumpers, or plastic lumber – all unrecyclable products. “Recycled’ in this case merely means “collected.”

A bottle can become a fabric, but a fabric can’t become a bottle – or even another fabric, but we’ll get to that later. There are far too few exceptions to this rule.

Plastic has what’s called a “heat history”: each time it gets recycled the polymer chains break down, weakening the plastic and making it less suitable for high end use. PET degrades after about 5 melt cycles. This phenomenon, known in the industry as “cascading” or “downcycling,” has a troubling consequence. It means that all plastic – including the tiny proportion that finds its way into another bottle – “will eventually end up in the landfill,” said Jerry Powell, editor of Plastics Recycling Update.

The technology exists to recycle most kinds of plastic, but a lack of infrastructure prevents all but the most widespread kinds of plastic from being recycled. Collection is expensive because plastic bottles are light yet bulky, making it hard to efficiently gather significant amounts of matching plastic. For recycling to work, communities must be able to cost effectively collect and sort plastic, and businesses must be willing to accept the material for processing. So no matter whether a particular plastic is in a form which allows it to be melted and reused, something is only recyclable if there is a company out there who is willing to use it to make a new product. If there is no one who will accept the material and make a new product out of it, then it is not recyclable.

Only a few kinds of plastic have the supply and market conditions that make recycling feasible. With plastics in particular, how the plastic particles are put together (molded or extruded) changes their chemical make up and make them non recyclable in certain applications. Some bottles make it to a recycler, who must scramble to find a buyer. The recycler often ends up selling the bottles at a loss to an entrepreneur who makes carpeting or traffic strips – anything but new bottles.

Recycling reduces the ecological impact of plastic, but it remains more complicated, more expensive and less effective than other parts of the recycling industry. No matter how many chasing arrows are printed on plastic products, it doesn’t change the fact that plastic is largely a throwaway material.

Next week: what is the plastic industry doing to create a stronger recycling market for its product?

What an awesome way to explain this-now I know evyeithrng!

You actually make it seem really easy together with your presentation however I to find this topic to be

actually something which I feel I would never understand.

It seems too complicated and very broad for me.

I’m looking ahead to your next post, I will attempt to get the grasp of it!

Hi Danial: The post you reference was actually posted on 4.28.2010, so the follow up post (Plastics: Part 2) was posted on 5.5.2010. You can find the list of topics on the right hand side of the blog, and find the subject, “plastics”. If you click on that, all the posts on plastic (including Plastics: Part 2) will appear.

I needed to discuss this article, “Plastics – part 1 | O

ECOTEXTILES” optionsonstock together with my best good friends on fb.

Ionly wished to distribute ur outstanding publishing!

Thanks, Carrie

Hi Hollis: We write this in the hopes that people will share it! Thanks so much for distributing…

I do not know whether it’s just me or if everyone else experiencing problems with your website. It appears as though some of the written text in your posts are running off the screen. Can somebody else please provide feedback and let me know if this is happening to them too? This could be a problem with my internet browser because I’ve had this happen previously.

Thanks

It’s a shame you don’t have a donate button!

I’d without a doubt donate to this brilliant blog! I

guess for now i’ll settle for book-marking and adding your RSS feed to myy Goole account.

I look forward to new updates and will share this website

with my Facebook group. Talk soon!

Thanks for your thouhgts. It’s helped me a lot.

my father worked in the polymers sciences industry all his life and has always been an opponent to the “greenwashed” idea of recycling plastics. I thought he was just defending his field and reacting against what he saw as the naive environmentalism of his daughter, but, much to my dismay, a lot of what he said about downcycling, energy use, heat history, etc was echoed by your posts. disappointing, but no surprise that the plastics PR folks have managed to turn the environmental issues to actually promote more consumption of plastics. i would like to ask if there have really been no improvements to recycling methods and demand since the 90s to make it a more efficient, feasible process? am i still just being naive when i toss my plastic yogurt containers into the recycling bin? i know your specialities are mostly textiles, but in your research of this topic, have you come across any viable biodegradeable alternatives for packaging (i.e. chitosan, fungal plastics, etc) or are those just novel concepts for now? thanks for a well researched post, as usual. i’m based in seattle too!

The recycling rate for plastic bottles grew to 31% in the USA in 2014, yet according to the EPA the recycling rate for all plastics is still only about 9%. The rate for plastic bottle recycling has been increasing slowly over time, yet virgin materials are still cheaper than using recycled plastic – and as we say, cheap is what most manufacturers are after! In the EU, a policy called “extended producer responsibility” shifts the burden of recycling from taxpayers (as it is in the USA) to companies. The USA is taking a look at these types of schemes since voluntary recycling, paid by municipalities, doesn’t seem to be working. As for bioplastics, there is much in the media about new centers (such as the NSF Center for Bioplastics and Biocomposites, funded by industry ) and predictions for phenomenal growth, but so far I don’t know of any that lead the field. One problem, as I see it, is the fact that so many plastics are designed for specific end uses, such as packaging (needs to be flexible, lightweight) vs. bottles (needs to hold its form). As far as I can tell, chitosan and fungi, though promising, are not yet mainstream